During the period May 9 to May 21, 1969, contact with the enemy, mostly NVA, was very heavy. Intelligence reports indicated that a minimum of one NVA Battalion and elements of an undetermined number of other enemy units were using the northeastern portion of the Arizona area as a staging area for attacks on U. S. installations north and east of the Song Vu Gia River. Intelligence indicated that a planned enemy attack on friendly positions located at Hill 65 and the bridge at Phu Loc 6 was aborted because of the heavy losses that the enemy sustained in our action to quickly react and attack.

During the period May 9 to May 21, 1969, contact with the enemy, mostly NVA, was very heavy. Intelligence reports indicated that a minimum of one NVA Battalion and elements of an undetermined number of other enemy units were using the northeastern portion of the Arizona area as a staging area for attacks on U. S. installations north and east of the Song Vu Gia River. Intelligence indicated that a planned enemy attack on friendly positions located at Hill 65 and the bridge at Phu Loc 6 was aborted because of the heavy losses that the enemy sustained in our action to quickly react and attack.

The NVA was heavily fortified in bunkers, connecting trench lines, and surrounded by several rows of tree lines. The temperature and humidity for the month were extreme. The average high temperature for the month was 103 with a low of 84. Only .59 inches of precipitation was recorded.

Hotel company had been up on Charlie Ridge running patrols when we were called to walk down off the mountain and move into a sweeping position in the Arizona Territory. We had walked (humped) almost the whole day. It was late in the afternoon, May 11, 1969, Mother’s Day back in the States, when we encountered the enemy. Hotel Company encountered four bunkers occupied by NVA armed with automatic weapons. After the fierce battle with 19 NVA KIA, Hotel Company secured the bunkers.

Sometime in the middle of that firefight, I passed out and fell to the ground. I had about 78 lbs. of weight on my back, carrying my normal gear and the PRC-25 radio. Doc Rudy, my corpsman, tagged me that I had a heat stroke and medivaced me with eight other wounded men from Hotel 2/5 and three USMC KIA.

I remember coming to twice during the medivac. The first time, Doc Rudy was leaning over me, trying to get some fluids into me. A moment passed and the next time I came to was when I was laying out on a wooden board somewhere outside. I saw blue sky and someone holding a garden hose. Weird I thought. I felt numb. Another moment went by, and it was four days later. I had been medevacked to the Da Nang Naval Hospital. It was four days later when I came out of my coma. I sat up and yelled, “Am I OK?” I did a physical inventory to see that I still had all my body parts. And I did! I did have bandages covering both of my forearms.

A doctor came over to my bedside and said, “welcome back Marine”. He explained that I had been in a coma for four days. When they took me out of the helicopter, they cut off all my clothes with large electric scissors and packed my whole body in ice except for my mouth, nose, and eyes. Every 10 minutes, they hosed me off with a garden hose of water, then let my body dry naked outside on a stiff wooden board sitting on some sawhorses. Then repacked me in ice again and did this procedure several more times until they were satisfied my body temperature had dropped into a safe zone.

They removed the bandages off my forearms. Wow! My gook sores were almost completely healed up. No more open sores. They bathed me every day I was in the hospital. They allowed me to walk around the hospital ward but only with another person standing beside me. I got a good night’s sleep that fourth night, feeling safe and resting peacefully.

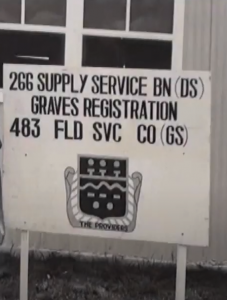

The fifth day, Friday, May 16th, I was still in the hospital; I received orders to report to Graves Registration. That wasn’t good news. The hospital gave me brand new clothes, a new starched cover, a new belt, and brand-new combat boots before they sent me on my way.

I was to help identify three bodies that I knew from my company who had died three days earlier. Pfc Patrick Best, Pfc Danny Fann, and 2nd Lt. Theodore Vivilacqua were together when they were hit with incoming rockets and mortars. The reason they needed me at Graves Registration was because one of the bodies had his face missing and there were two different names on two separate dog tags attached to his body. I knew all three of these guys from my company. Teddy was my company commander, Patrick, another radioman. Best was new and had only been with us a month in Nam. We spent some time together in fox holes and walking near each other while on patrols.

I was to help identify three bodies that I knew from my company who had died three days earlier. Pfc Patrick Best, Pfc Danny Fann, and 2nd Lt. Theodore Vivilacqua were together when they were hit with incoming rockets and mortars. The reason they needed me at Graves Registration was because one of the bodies had his face missing and there were two different names on two separate dog tags attached to his body. I knew all three of these guys from my company. Teddy was my company commander, Patrick, another radioman. Best was new and had only been with us a month in Nam. We spent some time together in fox holes and walking near each other while on patrols.

After I left that facility, I caught a ride over to the staging transportation area to catch a helo back to An Hoa. It was late in the afternoon, and I just missed the last CH46 helicopter headed for An Hoa. I had to spend one more night in Da Nang. That night, at the place I was being housed, they had some music entertainment for the guys. There were Marines, Navy, and Army guys along with a few ARVNS, and a couple of Australian soldiers all waiting to catch helo rides or a convoy going somewhere out of Da Nang to their assigned units. This was the first time that I realized that there wasn’t just American’s fighting in this war.

After grabbing some hot food at the small mess hall, I joined many of the guys also waiting for their rides and went into a closed in air-conditioned building. There were seating and a stage with a band getting ready to perform some music. The music entertainment was certainly a welcomed change from being out in the bush. I was given one of those cardboard cameras by one of the nurses at the hospital when I left, so I took these pictures of the band.

This was my first experience ever of seeing and hearing an international band perform. I don’t know where they were from, whether they were Vietnamese, Thailanders, Korean, or elsewhere. What impressed me about them was they would sing a Beatles song, first in English with their heavy accents, then sing it again in Vietnamese, then again in Korean. This went on for three hours listening to the top thirty pop songs of the sixties in multiple languages.

It was a bit shocking seeing a young girl my age up on the stage singing with a beautiful voice and a beautiful figure. She was also smart, singing the same song in three or four different languages.

It was amazing that listening to that music actually helped me forget about the war for a little while.

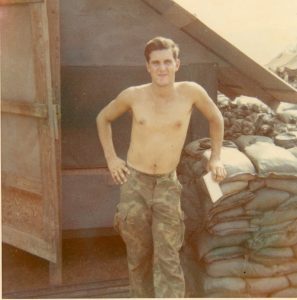

This is a picture of me shortly after getting out of the hospital with a heatstroke in An Hoa. I was placed on “no duty assignments” for four weeks. Most doctors send heat stroke/coma patients to Germany or Okinawa to recover, but I begged to get back to my unit. So, I got four weeks of doing nothing in An Hoa. No foxhole duty, no gate duty, no tower duty, no work parties.

This is a picture of me shortly after getting out of the hospital with a heatstroke in An Hoa. I was placed on “no duty assignments” for four weeks. Most doctors send heat stroke/coma patients to Germany or Okinawa to recover, but I begged to get back to my unit. So, I got four weeks of doing nothing in An Hoa. No foxhole duty, no gate duty, no tower duty, no work parties.

This time off was really hard on me. I wanted to be back with my company out in the Arizona Territory. I know they needed radio operators. I missed my radio, my M16, my .45 pistol. I felt a little weak, but I was ready to go. I kept asking if I could get a release from the doctors/medics but was told “no” everyday I asked.

Survivor’s guilt began to sink into my thinking. I can’t remain here in the rear, napping, taking it easy, and doing absolutely nothing while my platoon and company were out in the bush on patrols and sweeps getting shot at. I wanted to get back out there and kill as many of them as I could find. What the heck was so wrong with me that I wasn’t good enough to be out with my team? Those three guys died a few days ago, and I should have died with them. If I hadn’t gotten the heatstroke, I would have been with them. But for some reason, God spared my life and put me here in An Hoa doing nothing.

After five days of doing nothing, I was going crazy. I would go walking outside my tent and walk around, although I was restricted to my tent billet. The only thing inside of the hot billet was cots lined up on two sides with five feet of space between the cots. The side windows were canvas, so they were rolled up most of the time.

I asked any NCO or officer around the place if I could help them in any way. I figured if I did only mental work to help and no physical labor, I’d at least be of help to someone and not get yelled at for doing any physical work. After a day or two of observing how things were working around the Hotel Company rear area, I found that no one was paying any attention to the mail piling up. It was piling up and not getting distributed because no one really knew where people were at. Many were out in the bush, some were medivaced out of country, some in hospitals, some on R&R, some like me displaced temporarily.

Mail was getting piled up, especially the small packages that came in the mail. Once mail was sent out to the bush, no one wanted to carry the excess mail or packages for return mail. So, the mail began to sit for days and a week or more before it got sorted or passed out. I jumped in and began sorting the mail and asking where so and so was at. Some pieces of mail for a few guys had been sitting around for over a month. They weren’t with their company. A few guys were on R&R, some guys were in prison or jail. Some were KIA. Some were still in a hospital in Da Nang. Some guys had been reassigned from one company to another when they got back from R&R or from being medivaced, and their mail didn’t get to them.

I took it upon myself to begin talking with the corpsmen/doctors, food staff, supply guys, the Chaplin and everyone else and began compiling a list of names of guys who had mail getting old and trying to determine where these guys were so I could get their mail forwarded to them.

This passion to get the mail out to the guys went on for three weeks and during that time, the Sargent Major in charge of the 2/5 battalion, took notice of what I was doing!