Click on this text line to view Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics

Body Count Measurements to Determine Vietnam War Success

US Marines Killed In Action in Vietnam = 14,836

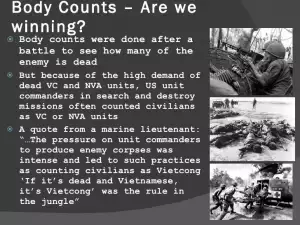

Since the goal of the United States in the Vietnam War was not to conquer North Vietnam but rather to ensure the survival of the South Vietnamese government, measuring progress was difficult. All the contested territory was theoretically “held” already. Instead, the US Army used body counts to show that the US was winning the war. The Army’s theory was that eventually, the Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army would lose after the attrition warfare. This “body count” concept carried over to the Navy and the Marine Corps as well.

Since the goal of the United States in the Vietnam War was not to conquer North Vietnam but rather to ensure the survival of the South Vietnamese government, measuring progress was difficult. All the contested territory was theoretically “held” already. Instead, the US Army used body counts to show that the US was winning the war. The Army’s theory was that eventually, the Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army would lose after the attrition warfare. This “body count” concept carried over to the Navy and the Marine Corps as well.

According to historian Christian Appy, “search and destroy was the principal tactic; and the enemy body count was the primary measure of progress” in General Westmoreland’s war of attrition. Search and destroy was coined as a phrase in 1965 to describe missions aimed at flushing the Viet Cong out of hiding, while the body count was the measuring stick for the success of any operation.

The combination of geopolitics and geography meant that there were no clear “front lines” in the conflict, as the US military was familiar with it from its experiences in WWII and Korea. traditional measures of military progress such as capturing territory or taking a hill were practically meaningless. Without this traditional means of gauging success, the US Army high command had to find a new way of reporting their strategic situation.

The “body count” strategy was implemented in the aftermath of the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965. the battle featured a new experimental US doctrine where ground troops were inserted via helicopter into areas with heavy enemy presence and by virtue of airborne support and overwhelming firepower was able to inflict tremendous casualties against superior numbers with a relatively small force.

General Westmoreland of the US rallied to turn the tide and stem the losses suffered in the South by making US involvement more open-ended. He reasoned that US military strength existed primarily in its offensive capabilities because of the nature of US military schooling. His plan was to “seize the initiative” to destroy guerrilla and organized forces of the North (read: search & destroy). This phase of engagement would require the continued commitment of the US (keep giving us money, soldiers, and weapons) and would end when the enemy was thrown on the defensive, exhausted, low on resources, and unable to launch insurgent or organized attacks. (Read: go on the offense by seeking out enemy forces within South Vietnam, but don’t actually invade North Vietnam).

Essentially Westmoreland reasoned that US superiority in warfare technology and resources would eliminate more bodies than the North could replace. Part of his attrition strategy did also include recruitment strengthening in the South (primarily to discount another body for the North). American soldiers and technology would advance to wipe out the bulk of the North Vietnamese Army’s (NVA) organized forces and ARVN would be relegated to taking over defensive roles in the South and bolstering recruitment. Attrition was to be supported with heavy firepower and bombing that would in theory suppress enemy safeties and hiding spots.

Here; after all that explaining is why Body Count was the favored metric of success. The body count concept affirms Westmoreland’s strategy of attrition and gave tangible “evidence” of winning the war. The lack of fortified positions to take over in the brush of Vietnam and the extremely rugged nature of the terrain made it difficult to really say: “this dense jungle is controlled by us” or “this air force base is now controlled by us”. However, Body Counts almost always sounded favorable to the US and gave the illusion that the US was winning.

Sources:

Moore, Harold G., US Army Col. (ret.), We Were Soldiers Once… And Young: Ia Drang – The Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam

Sheehan, Neil, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam